LOST—AND FOUND

Things get lost: keys, glasses, papers, treasure…. Particularly the kind of papers that are, themselves, “treasures”: documents that give us insight into a historical situation, or proof of an extraordinary occurrence, of photos that establish a significant connection.

In the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, we recently came across such a treasure: a tiny, vintage, color snapshot—the image size being no bigger than a couple of inches across. The scene shows the great Modern architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, seated at the right side of a table. Behind him are several figures—students, we believe—and one of them is Phyllis Lambert. [Phyllis Lambert has made many profound contributions to architecture—not the least of which was to move her family to select Mies to design the Seagram Building. Later, she went on to attend architecture school, practice architecture, and found the great Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA).]

In front of Mies, on that table, is a drawing—and, reaching out from the left side of the photo is an arm, pointing to the drawing.

But whose arm? And where and under what circumstances was the photo taken? And what’s all this got to do with Rudolph?

We decided to investigate! But—before we reveal what we contend are the answers—it’s worth reviewing a few Mies-Rudolph connections.

MIES AND RUDOLPH

In one of our earlier posts, “The Seagram Building—By Rudolph?” we wrote about how Rudolph was—very briefly—on the list of the many architects that were considered for the Seagram Building. And in another post, “Paul Rudolph: Designs for Feed and Speed,” we showed both Mies’s and Rudolph’s comparable designs for highway/roadside restaurants.

We were also intrigued to learn that Paul Rudolph had been asked to be Mies’s successor at IIT! This is mentioned in “Pedagogy and Place” by Robert A. M. Stern and Jimmy Stamp, the grand history of Yale’s architecture program. That information-packed volume covers a century of architectural education, 1916-2016—and includes a large chapter devoted to the era when Rudolph was chair of the Architecture department (1958-1965).

The book relates:

Yet even before the Yale appointment, Rudolph was so respected as an architect-teacher, despite his youth, that in 1955 he was asked to succeed Mies van der Rohe as head of the architecture program at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Rudolph did initially agree to take the position, but a few weeks later withdrew. It’s tantalizing to muse about what might have happened to mid-century architectural culture—especially in America—had he gone ahead to become head of ITT’s program. [One thing for sure: there would have been no Yale Art & Architecture Building—and the world would have been deprived of one of the greatest of Modern architectural icons.]

MIES’S VISIT TO YALE

At the age of 39, Paul Rudolph received his appointment to become chair of Yale’s architecture school and took office in 1958—a very young age, in that era, for such a position. One of the ways that he began to energize the school was to bring in a great diversity of instructors and guest critics (“jurors”)—and the book lists names of the many luminaries that he invited to the school: practitioners, teachers, and historians that were either already famous, or would later become so. Among them: James Stirling, Philip Johnson, Peter Smithson, Alison Smithson, Reyner Banham, Bernard Rudolfky, Ulrich Franzen, Edward Larrabee Barnes, John Johansen, Ward Bennett, Craig Elwood, and Sibyl Moholy-Nagy. Stern and Stamp also note:

…with the help of Phyllis B. Lambert (b. 1927), a reluctant Mies van der Rohe came to New Haven as a visiting critic for a portion of the fall 1958 term.

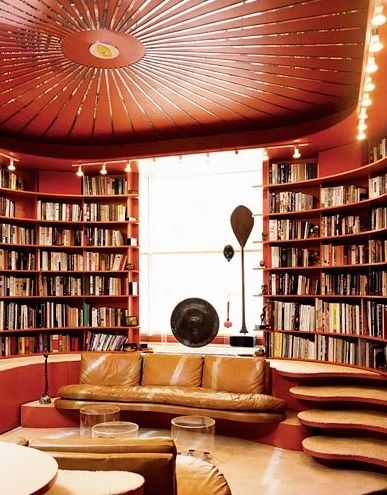

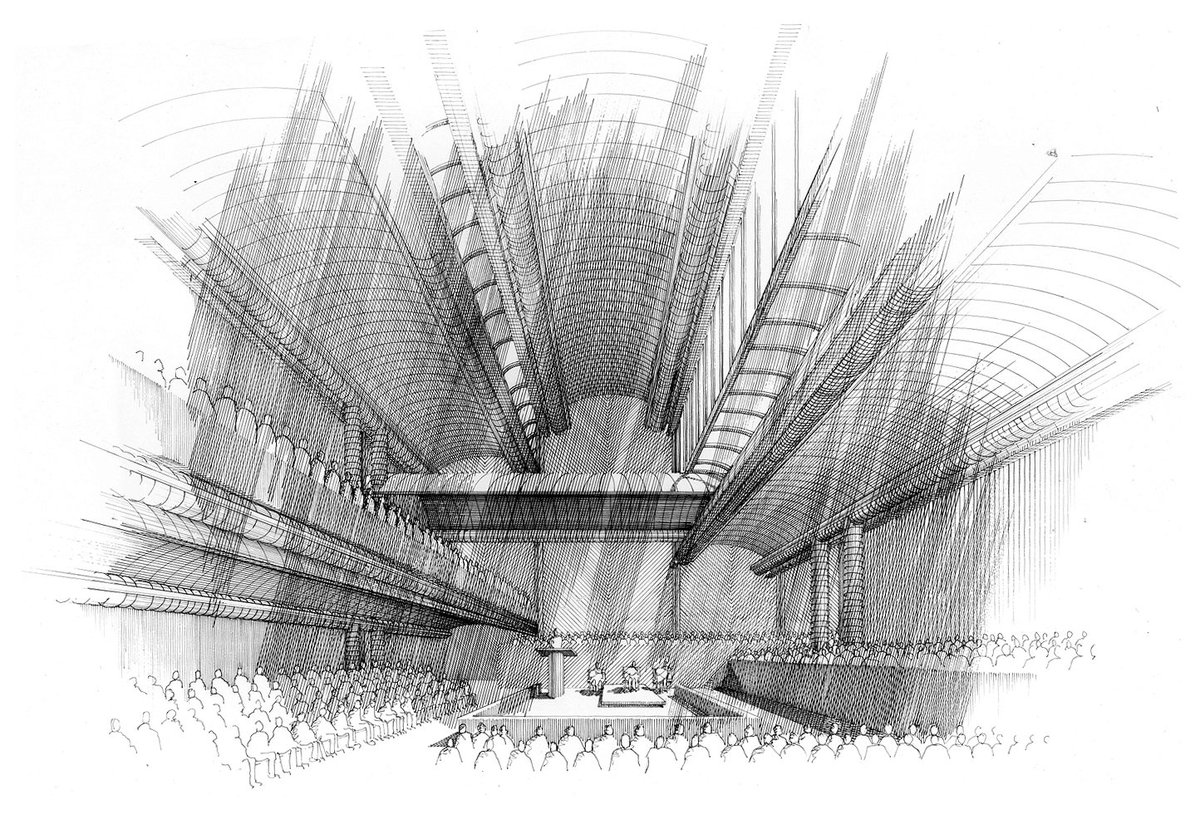

And among the book’s copious illustrations, there’s a photograph of Mies reviewing the work of Yale students.

Timothy M. Rohan’s magisterial study of Paul Rudolph’s life and work, The Architecture of Paul Rudolph, also mentions Mies’s visit.

OUR PHOTO…

In attempting to identify the owner of the arm, in our mysterious photo, we looked at it with a magnifying eye loupe. Rudolph was known for his tweedy suits, sometimes in earth-tone hues or grays—or something approaching a blending of the two. Under magnification, the material of the jacket sleeve which clothes that arm seemed to have the right color and texture—but, beyond that observation, we couldn’t arrive at much of a conclusion.

So we reached out to Ms. Lambert: we sent a scan of the photo and asked if she recalled whose arm it might be, the occasion of the photo, and whether it might have been made during a visit by Rudolph to IIT—or—a visit by Mies to Yale.

Phyllis Lambert graciously responded, via her executive assistant, who sent us the below note:

Ms. Lambert Lambert has seen the snapshot and below are her comments:

I cannot identify the students. I was at Yale from when Rudolph was dean and Mies visited for a few days at that time. And I also saw Albers walking in the street and talked briefly with him. To my knowledge, Rudolph never came to IIT when I was there.

That overlaps with what is in Stern’s and Stamp’s book, and Rohan’s, about Mies coming to Yale. Moreover, we’ve also never heard of any visits by Rudolph to IIT.

But there’s more. Ms. Lambert’s executive assistant had a further gift for us, and she writes:

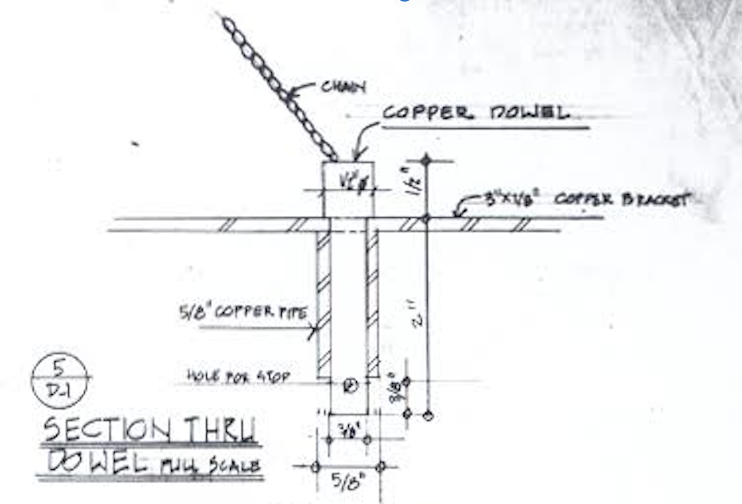

About the picture size and luminosity:

Attached is a scan of the picture we worked on a bit, bigger and with more luminosity which reveals a bit of the unidentified person’s face.

Here’s the enhanced version which they sent: