Our Search for the Unknown (and 4 Newly Discovered Paul Rudolph Projects!)

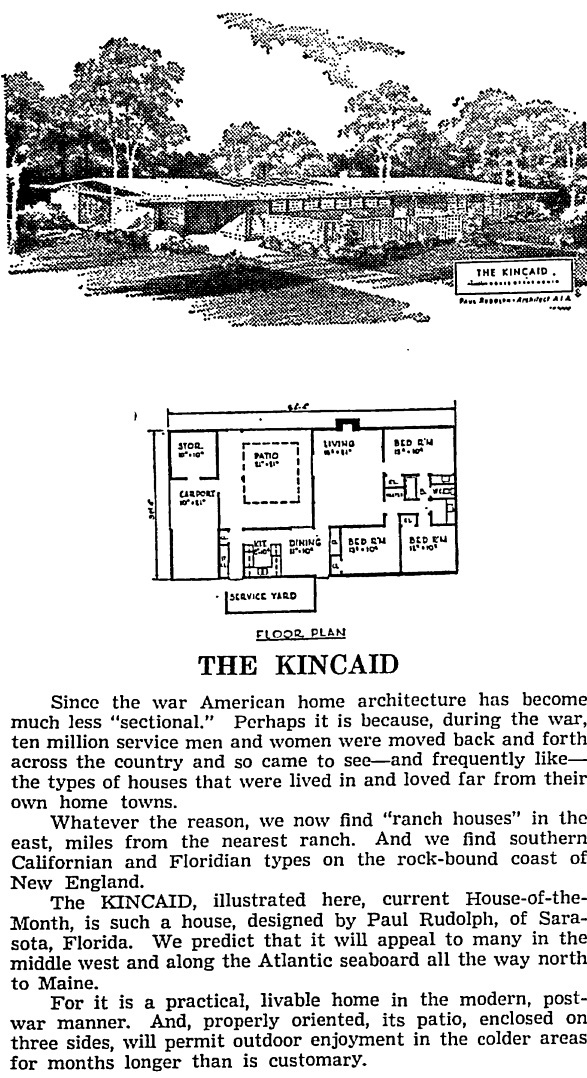

The “Kincade” is the name of a mid-1950’s house design by Paul Rudolph. It was published as a “Home-of-the-Month”—apparently part of a series of home designs available to the public through lumber yards and construction supply companies. This image is from a 1954 article in the Denton Journal.

WE HAVE A LITTLE LIST….

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is making a complete record of all Rudolph’s projects—and currently there are over 300 projects on it. To the maximum extent possible—that is to say, findable—for each project we try to include comprehensive info: its exact location, names of all participants, budget, primary materials, drawings, pictures of models, construction photos, as-built photos…

BUT HISTORY IS HARD

You’ll notice that we said “currently”, for the list is still still growing. Now that may seem to be a strange thing to say about the work of an architect who passed away over 2 decades go: it’s not as though he’s kept creating more works that we need to keep track of. So it’s reasonable to assume and ask: Wouldn’t the record be complete by now?

Well, it’s not that simple.

Creating an accurate catalog of all of Paul Rudolph’s work, and finding the above-mentioned full range of data & images for each project, is a more challenging task than you might expect...

On the one hand:

Rudolph did not make it easy for us. Yes, he made his own official lists of commissions and projects—and those would appear in monographs, or be given to journalists or potential clients. Across a prolific career that lasted more than half-a-century, Rudolph kept editing those lists: adding new projects as they arose, and deleting ones which he considered less important. That’s a natural process for any architect—but some of the projects on those ever-evolving lists are just names to us, without barely any traces in books about him (or the hundreds of articles written about Rudolph.)

Here’s an example. One list includes “Dance Studio and Apartments” For that project, who was the client and what was the scope? All we presently know about that project is that it was from 1978, and was located somewhere in the Northeast. Was a design offered? If you look at our “Project Pages”—and we make one for each Rudolph project that we know of (the’re like our on-line file for each of Rudolph’s works)—you’ll find that some project pages are rich with information & images. But our page for the “Dance Studio and Apartment” is just a “place-holder”, currently containing only the most skeletal of info. We’d love to see some photos or drawings—but none have been found [yet.]

One prime source, for those researching Paul Rudolph, is the Library of Congress’ archive of Rudolph drawings & files: it runs to hundreds-of-thousands of items (all made before computers entered architectural offices—so they were drawn by-hand or typed). While there’s a general inventory, the only way to really know what’s in the archive is to go there and look—so we make repeated visits to Washington to do research within those rich holdings. [Perhaps, in one of those research trips, we’ll find out something on that “Dance Studio and Apartment.” ]

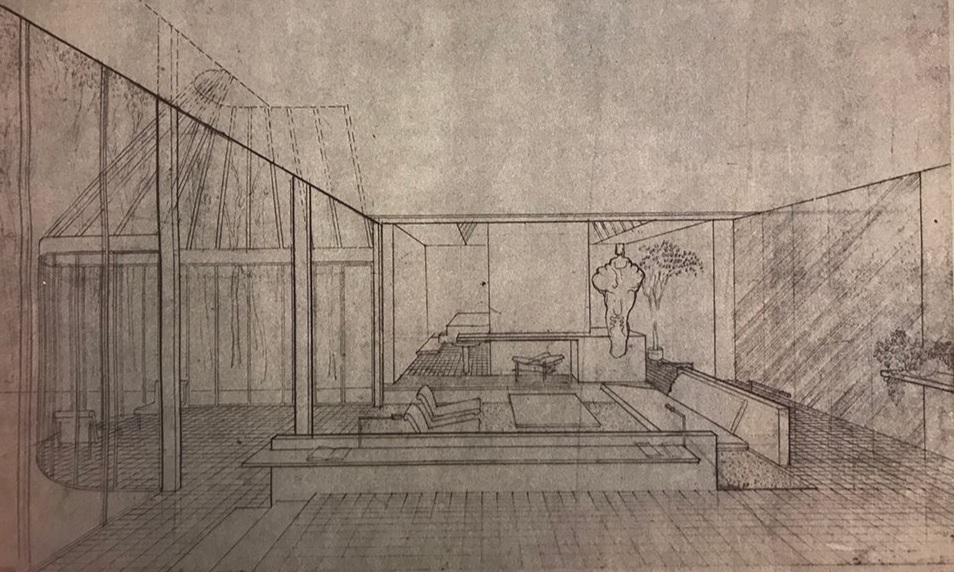

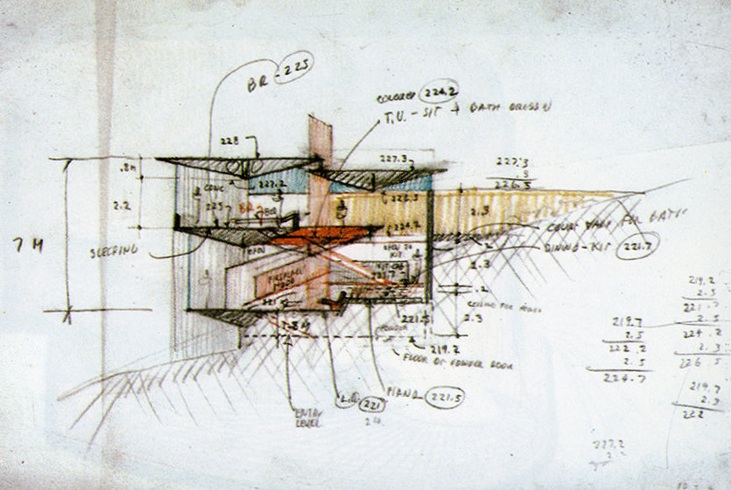

Sometimes we do have just a little info about a project—a single drawing—which makes us want to see more. For example: Rudolph had international commissions, including a few for Europe. A magazine showed a drawing for a house proposed for Cannes: the Pilsbury Residence. But that drawing is all we’ve ever come across about it. What was the project’s history? Was it built? We’re keen to find out.

The Pilsbury Residence, a design from 1972. All we’ve seen—so far—of this project is this intriguing section sketch by Rudolph. It was published in a Japanese architecture magazine (in an issue entirely devoted to Rudolph’s work), and was designed for Cannes, France. It is one of Rudolph’s few works for Europe—N.B the dimensions seem to be in metric. The project’s name and proposed location is all that we know about it—so far. We’re hoping future research will reveal more. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Then there are the times when it is clear that something’s been built—but we know little else. For example: Rudolph was asked to design an office for a prominent Texan, Stanley Marsh III, and we’ve been able to find a single image of it for our project page—but, so far, that’s all we know.

The office of Stanley Marsh III—an interior Rudolph designed in Amarillo, Texas in 1980. Marsh (1938-2014) was quite a character, and—in his capacity as art patron—is most famous for commissioning the legendary art installation “Cadillac Ranch” by the art-design group, Ant Farm. Marsh also commissioned Rudolph to design a television station (also in Amarillo) that was constructed in the same year as the above office. Marsh was a great collector, as one can see in the works accumulated in this photo. But what was Paul Rudolph’s involvement in this office’s design? Modulightor—the lighting fixture company that Rudolph co-founded, and whose system of fixtures he designed—was started about the time of this project. So might the lighting system (seen on the office’s ceiling) be one that Rudolph planned and then specified from Modulightor? Are there other aspects of the office, not viewable in this shot, that Rudolph designed? More mysteries to be investigated!

Moreover, Rudolph was not the best record-keeper. Yes, his office [or rather, offices—as he started/re-started several, as his career took him around the country] had the sort of record-keeping systems which were standard for architectural offices in the post-World War II era of professional practice in the US. They maintained “time sheets” (or cards) to keep track of the hours that each staff member devoted to a project, as well as notes and files of various kinds were made (about meetings with clients, sketches, bids, construction field-reports, engineering, correspondence, etc..). But there was nothing like a company historian to keep a meticulous record of what was going on—and, going through the files, one gets the feeling that Rudolph was so busy that they just recorded (and kept the papers) of what was absolutely necessary to keep their various projects moving along.

A blank time card from from Paul Rudolph’s office—a fairly standard example of the type of record-keeping that would be used in architects offices in the US. Staff would fill these out to show how much time they’d devoted to each project, and submit them weekly. The resulting info would be used for billing. Image © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

On the other hand:

Doing this research brings a continuous (and delightful) sense of adventure! As we come across new projects, images, and documents, we discover more layers of Paul Rudolph’s creativity—and also have an ever-enlarging sense the great range of design challenges with which he was willing to engage.

OUR FOUR LATEST DISCOVERIES: PREVIOUSLY UNKNOWN (OR “UNDER-DOCUMENTED”) RUDOLPH PROJECTS

In the last few weeks, we’ve come across 4 previously-unlisted projects—or ones with so little info (“under-documented) that they remain mysteries to be solved.

ONE: “KINCAID” HOUSE DESIGN

Newspaper articles from 1954 and 1955 show a house designed by Rudolph, the “Kincaid”. They were part of a series, the “House-of-the-Month”. These were a collections of house designs—often by skilled architects and well-thought-out, with good layouts, and planned for efficient construction. They were offered to the public via advertisements and books. Such books, which usually showed a dozen-or-more different designs (of various styles, sizes, and budgets) were available at lumber yards, building-supply stores, and newsstands. The info on each house design usually included a perspective rendering, floor plans, basic data, and a brief written description—and every house received a name. If one liked a house, complete plans & specifications could be ordered for a modest fee.

An example of a House-of-the-Month book: a collection, in booklet form, of available architectural designs for houses.”by leading architects.” A quarterly publication of the Monthly Small House Club, Inc,, this one is from 1951 (a few years before Rudolph’s “Kincaid” house came out.)

While, via this system, an architect did not get to make a custom solution for a client, he was able to exercise his creative ability to design a workable, affordably house that had a sense of style—and enough generic good qualities that it might appeal to multiple clients. So the advantage for the architect was that he might be rewarded with many small fees for the same design [Or perhaps he received a flat-fee from the publisher? Arrangements may have varied.] Such “plans service” companies continued to exist for decades—and even have a recent incarnation in the Katrina Cottages—and their impact on the American housing market would make an interesting study. Evidently, as shown by the “Kincaid,” Rudolph participated in this system—though on what terms (or what he ultimately thought of it) remains a mystery.

TWO: DANCE STUDIO AND OFFICES IN FORT WORTH

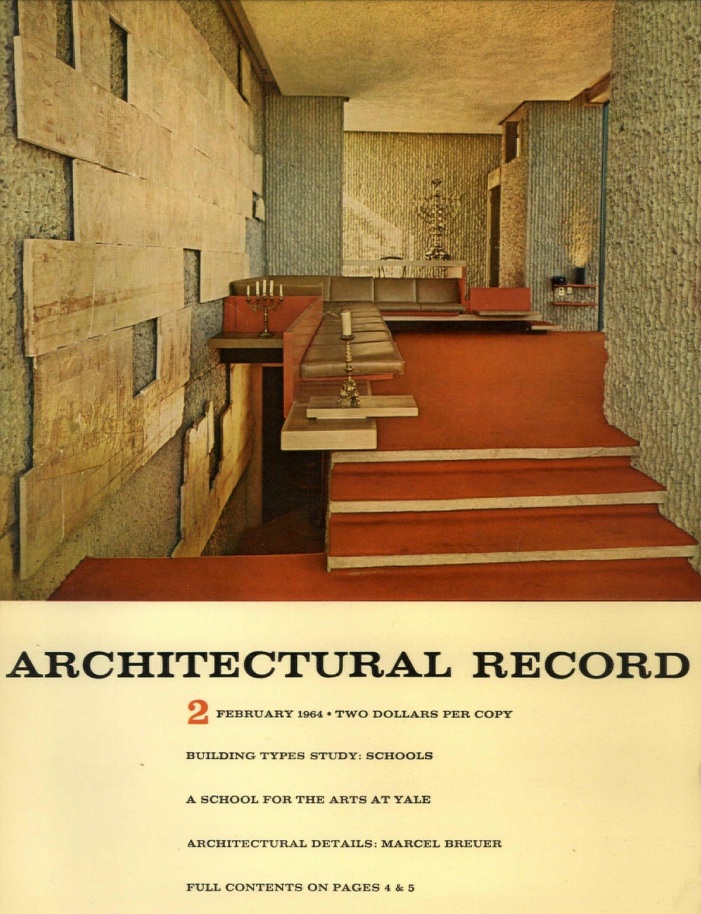

The May/June 1998 issue of Texas Architect ran an article surveying the work that Rudolph had done in Texas. Max Gunderson’s text reviews the origin and history of each project.

Texas Architect has been published since 1950, and you can access its full archive of back issues at their website. It was the above issue that included Max Gunderson’s excellent article surveying Rudolph’s work in that state.

In the course of speaking about one of Rudolph’s most splendid house designs—the Bass Residence in Fort Worth—he also mentions:

Rudolph would also design the Fort Worth School of Ballet for Anne Bass, a simple teaching/workspace and offices in a retail strip.

Since a great architect can bring “an extra something” to even the simplest projects, we’d love to see what Rudolph came up with here.

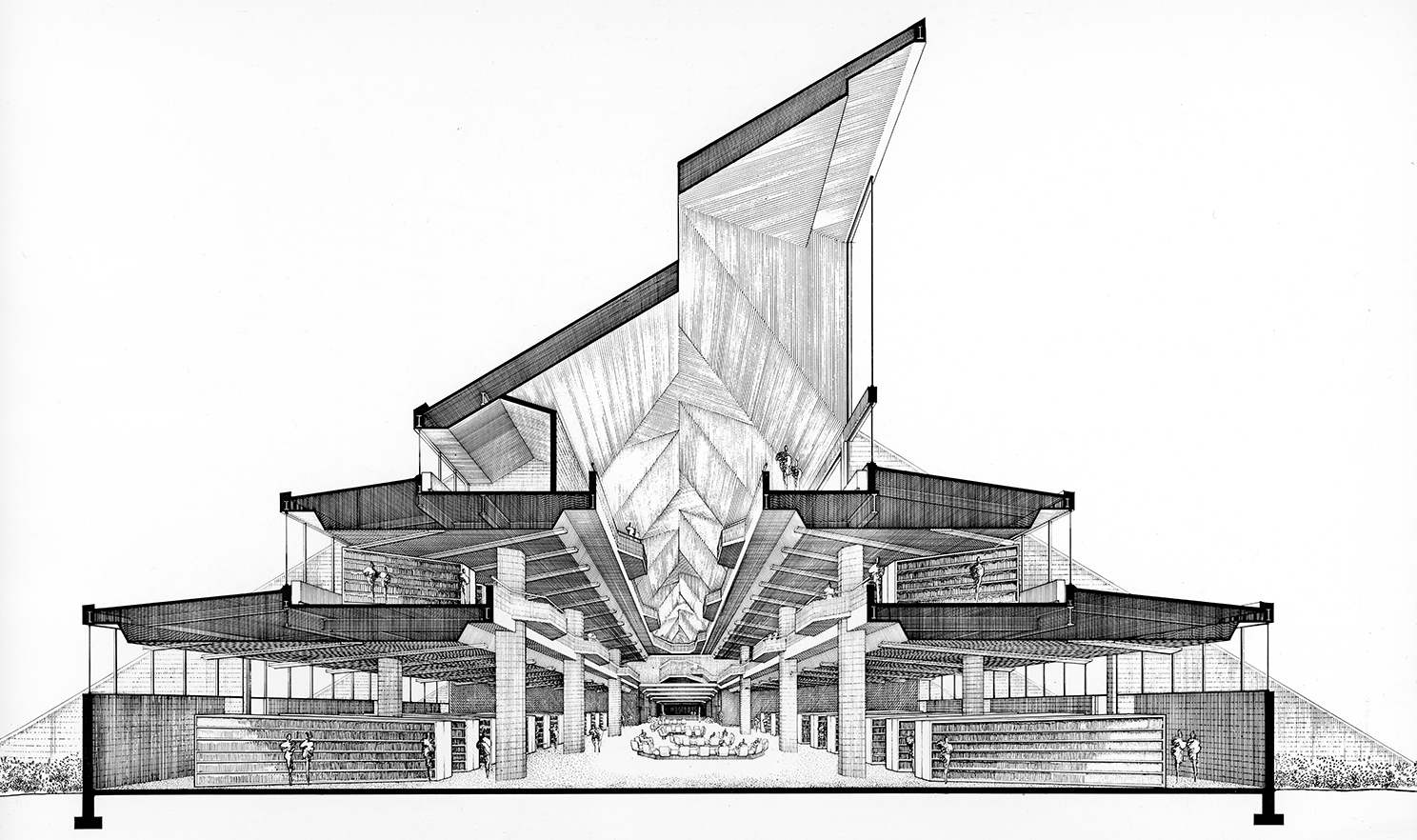

THREE: BAHRAIN NATIONAL CULTURAL CENTER

We’ve heard that Rudolph was involved in a project to design a cultural center for Bahrain. This may have been as part of a design competition. There’s a transcript of an oral history interview with Lawrence B. Anderson (1906-1994): he was an architect who was already well familiar with Rudolph—his firm was the associate architect, with Paul Rudolph, for the Jewett Arts Center at Wellesley (and that transcript has interesting things to say about that project.) Anderson participated in a 1976 jury to review the proposed designs for the Bahrain National Cultural Center, and in the transcript he speaks of the process and cultural context—but he doesn’t name the competitors or winners. So we don’t have a confirmation—at least from that one source—as to whether Rudolph was a competitor (of if he “placed”). We’d like to know more about this project—and, of course, we will welcome any “leads” that our readers submit.

By-the-way: it’s worth noting that, across his half-century career, Rudolph was involved in several projects for the mid-east. Among them: a US embassy for Jordan, a sports stadium for Saudi Arabia, and an apartment-hotel in Israel—none of which, unfortunately, reached construction stage.

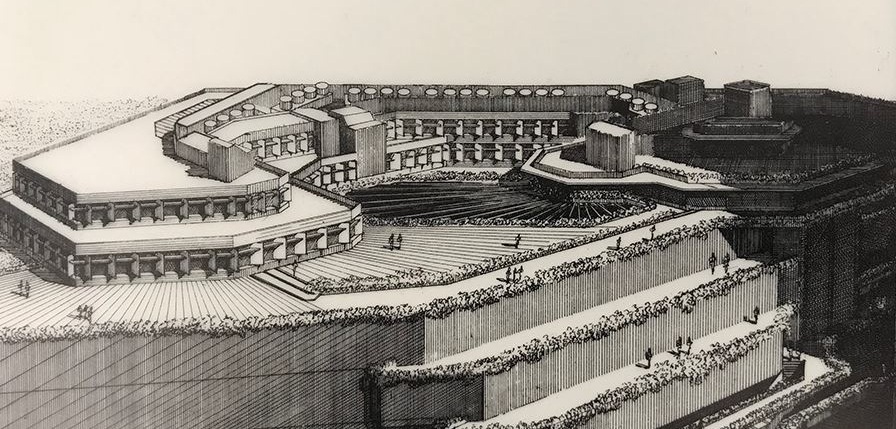

FOUR: HUNTS POINT MARKET, NEW YORK CITY

Hunts Point Market (or, more formally, the Hunts Point Cooperative Market), in New York’s borough of the Bronx, is one of the the largest wholesale food markets int the world—and a large portion of the food (produce, meat, and fish) consumed in the New York City metropolitan area is provided through it. Occupying 60 acres in the Hunts Point neighborhood, and it's annual revenues exceed $2 billion.

During the administration of NYC Mayor Robert F. Wagner, market facilities were constructed in 1962: a 40-acre facility with six buildings—and now the Market consists of seven large refrigerated/freezer buildings on 60 acres.

New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman look at architect's drawing of new Hunts Point Market during the 1962 ground breaking ceremonies in the Bronx, NYC. The year of this image, and the fact that Wagner was New York City’s mayor just prior to Mayor John V. Lindsay, suggests that the design shown is the market that was built prior to the announcement that Rudolph would become involved. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

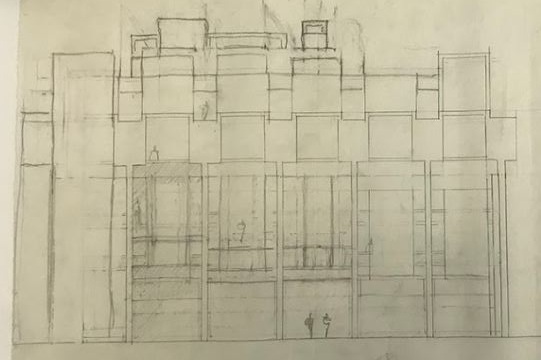

But it seems that during the administration of the next mayor (John V. Lindsay), it was planned that Paul Rudolph was to have some involvement in further development of the Hunts Point market facilities. At least that’s what a document, from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, seems to indicate. We’ve found a press release from the Office of the Mayor, dated May 2, 1967, in which Lindsay appoints Rudolph

“… as supervising architect for the Hunts Point food processing and distribution center. Mr. Rudolph will be responsible for the project design, for designing many of the market buildings in the project and setting all design and structural specifications for the development.”

Most of the rest of the press release praises Rudolph, and says nice things about the importance of the Hunts Point market and its location. But there’s not much more about the nature of the project, except the text again refers to food “processing”—so the new buildings, which Rudolph was to work on, might likely have accommodated facilities for the transformation of food (as distinct from marketing/distribution).

Lindsay was mayor during one of the city’s (and nation’s) most exciting and also most difficult periods, with his administration lasting from 1966-1973.. He is often evaluated as a a "good guy” with positive ideals, but one who was up against the tumultuous churnings of in NYC’s/country’s politics, economy, and culture in those tough and “crazy” years of the late 60’s-to-early-’70’s. This was richly shown in a 2010 exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, as well as the accompanying book.

It was NYC mayor John V. Lindsay who announced that Rudolph would be involved in the Hunts Point Market. Many aspects of the exciting and difficult years of his administration were on display in a 2010 exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, for which this was accompanying book.

Lindsay’s administration did have a number of innovative construction initiatives (preponderantly in housing)—and this Hunts Point project might have been one of them.

The further evidence of Rudolph’s involvement is an item in the archives of the Library of Congress: a photos of a rendering of the old (1962) market design, with some markings on it—and the Library’s notes say that it was donated by “Rudolph Assoc., Architects”. Below is a small image of it. We’d guess that means it came into their possession as part of the large body of Paul Rudolph material that he donated to them—but that’s only a reasonable surmise.

So this is another example of a project that deserves further research. Did Rudolph produce a planning study and designs for it? Why did it not go forward? We’ve heard that there’s an archive of papers related to the Lindsay years: perhaps they’ll have some further information? We’ll let you know if we find anything.

A tiny image, from the Library of Congress, found when researching the Hunts Point project. It appears to be the same architect’s rendering (not by Rudolph) as shown in the photo above, but with some additional marks on it. What makes it intriguing is that the library’s info on this print says that it was contributed by “Rudolph Assoc.” Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

WANTED: HISTORY DETECTIVES & TREASURE HUNTERS

If you love mysteries, and would like to help us learn more about these projects, we’d welcome your help!

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is always looking for volunteers—including those who’d enjoy tracking-down information on Rudolph’s “under-documented” projects (like these—but there numerous others). Or perhaps you know something about the above-mentioned projects, and would be willing to share that info with us.

We’re seeking to build an archive & database that students, scholars, building owners, designers, and journalists will really find useful—and your help on these research projects would be welcome! You can always reach us through:

![An exterior side elevation of the terminal building. The capsule-like control tower [another saucer?—perhaps Rudolph saw Wright’s renderings?] is in the background at the right. The building’s columns appear to flare outward at their tops: a form re…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1563827539259-S0MVUHOMK3FBK8X4W0EP/Airport+side+elevation.jpg)